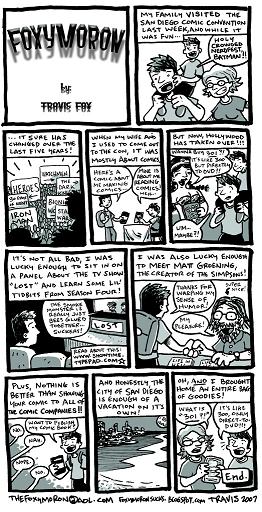

Travis Fox’s strip, Foxymoron, has been running for on Thursday’s for several years. In addition to his berth in the Star, he now also has a full page feature, Super Happy Fun Time in the paper’s weekly free distribution sister publication Ink which you can see at www.inkkc.com.

You can also review a whole slew of his past strips, along with the work of Casanova, Spottswood, and Cotter, on their joint blog at comicstripjoint.blogspot.com.

And, by the way, I’ve bl**ped a few choice words below to keep this blog “parent friendly.†Don’t let it get in the way of Travis’ point. And, yes, I see the irony.

Question 1: When did you first decide that you wanted to create your own comics for a living?

Well, let me make it clear that it was pretty much a pipe dream to ever really “make comics for a living.” I used to make mini-comics in middle school with my friend Jon Cox. We’d produce “special editions” with our logos cut out and the silver foil from Pop-Tart wrappers and the whole nine yards. He’d always tie his character Pauldo into situations with real trademarked characters like Batman and Jurassic Park and whatnot, but I was always afraid I’d get sued — you know, tons of lawyers prowl the middle schools to keep track of copyright infringement — so I’d stick with original adventures of Jerry the Wonder Boy and Axel.

The Wonder Boy was silly, with a kid in middle school who didn’t have much luck with the ladies and fought crime on the side, which never went well and ended up looking like an idiot most of the time. Pretty much my real life back in those days. Axel was more of the superhero fare with special weapons, lots of over-dramatic dialogue, and explosions. It gave me a chance to mess with perspective, cross-hatching, and basically made me feel like I was working on a “real” comic book.

It wasn’t until I got into high school, working on the school newspaper, doing more of a comic strip, that I realized I could really attempt this as a way to make money. More than the fifty cents we’d sell our comics for back in middle school, anyway.

Question 2: Who has had the biggest influence on you outside the comics industry, and how did they affect your life?

My high school art teacher, Gene McClain was the first to tell me that art was whatever you made it. Up until that point, I was worried about making it look like something other people would appreciate. Like drawing still life and worried about making it perfect, instead of just getting a general sense of the overall scene. He also let me pursue the comic aspect, which for an art instructor, was very rare. Most of them would ask, “Why do you have to give everything such a bold outline?” and things like that. I’ll never forget a professor at a community college who reminded me that, “Comics are low art.” That pretty much ended my relations with wanting to paint or consider myself an “artiste” with an inflated ego and all that baggage.

Question 3: Who has had the biggest influence on your comics career, and how has that person changed your work?

People around me get tired of hearing it, but I worship Matt Groening. Not because he gave the world The Simpsons and Futurama — although that would be enough on its own — but because to this day he still produces a weekly Life In Hell comic strip. He started it in 1977 and carries on for over 30 years later, not for the money, but the pure passion. It reminds me of what matters in life, and that even if I have to always have a second job to pay the bills, I’ll never stop doing comics.

Unlike a lot of other comic artists I know, I check out lots of other people’s work. I know some people feel like if they look at other artist’s work, it would influence their own — but luckily I’m not talented enough to pull that off. I just enjoy seeing the ways creative people deal with pacing, punch lines, and page layouts. Plus I like spending time with my family, since they pretty much write a lot of my strips.

Question 5: Describe your typical work routine.

I am totally a “Wait until the last minute and stay up until 2:00 AM the night before the deadline” type of personality. Also, and this pisses off a lot of my comic friends, I tend to just make it up as I go along. Rarely, and I mean raaaaarely, do I actually have an idea laid out before I go ahead and set up the panels and structure of the comic strip itself. More often than not, I’ll draw four panels, and figure out how to set up the punch line after the fact.

I usually pencil out the characters and backgrounds, but never the dialogue. I always just freehand that after the rest of the comic is inked. Back in the day, I used to shade the comic with pencils and greytones, but now I add all of that in Photoshop. I’m pretty good with Photoshop, aside from when it comes to having to correct something within the word balloons. I can always tell the difference between what I hand letter and what I have to correct later with a stylus.

Drawing the comic usually only takes me about an hour and a half at the most, but cleaning it up with the computer and adding either greytones or colors can take another two hours easily. I tend to spend the majority of the time looking for lil’ mistakes and fine-tuning the strip rather than working on making it funnier before I even draw the damn thing. That’s probably why I’m not more famous by now!

Question 6: What writing, drawing, or other tools do you use?

I adore the Pigma Micron pens. I usually use an 08 to outline everything and a 01 or 02 to write the dialogue. I also still use mechanical pencils to sketch out the strips, regular old typing paper to draw on, and Sharpies to ink in large areas of black. And, yes, I know it turns to yellow a few years later!

The kneaded eraser might just be the most incredible invention ever. Besides being a wonderful conversation starter whenever I use it out in public — “Is this clay? What? THIS erases things?! No way!” — it saves me from having to push down hard with a regular old eraser and leave behind tons of those lil’ eraser bits everywhere on the drawing itself.

I like making political observations and nailing hypocrisy — which I rarely get to do in my comic strips. I used to do this more in my self-published Foxymoron comic books. I also love to curse. Like a sailor. F**k f**kity f**k. That right there felt awesome.

It’s always a balance of what I think is funny and what the editors will let me get away with. For instance, we had a incident at our house where I told my four-year-old son, “Do not push Mommy’s buttons today, she’s not in a good mood.” And then, moments later, he walks up to her, touches her boob and runs away going, “Dad! I just pushed her button!” I did a comic about it, and we settled on Lex touching her arm instead. Even though it wasn’t sexual in any sort of way, you have to remember that there are 90-year-old grandparents still read the comics page and consider Blondie to be the standard of what’s cutting edge. [NOTE: We’ve included the original version here.]

Question 8: What has been the most rewarding project in your professional career – in or out of comics – and why?

It never got published outside of my own mini-comics, but my wife and I did a joint collaboration a month after 9/11 of her photography and my drawings about visiting New Jersey. Even though we didn’t get near “Ground Zero” or even step foot on New York, the memorials we saw, the “Missing” posters that lined the streets, the American flags everywhere — it was unlike anything I had ever experienced in my entire life. I’ll try to post these on Comic Stripjoint soon, so other people besides the 7 idiots who bought my old mini-comics can actually see the collaboration.

Question 9: We’ve all met very talented newcomers who are trying to get their first professional projects. What’s the best advice you’ve ever heard given to a promising new creator?

You have to want to do comics because you want to. Never expect to get paid or make a “living” off them. And don’t feel like your only options are doing comics for one of the major publishers or newspapers around the country. Get yourself a blog or Flickr page and just post them on your own!

Don’t worry about what’s popular or what the latest trend is, focus on creating a comic that you, yourself would enjoy. Make sure you’re creating something you’re completely happy with, otherwise it’ll seem more like work than an expression of your passion.

Of course, this is all for creating comics for your own. If you’re wanting to submit something to a larger company, you don’t get to play by the same rules. My only suggestion for you on that would be to focus on sequential art instead of pin-ups. Everyone can draw a kick-ass Superman fighting a robot, but it takes extra talent to show them having a stimulating conversation before they brawl.

Question 10: Time to get philosophical: What’s the most important “big idea” that you’ve learned in life – in or out of comics – and why is it important?

The only “big idea” I can think of is not taking rejection personally. It really hurts to work on a submission or comic book, show it off to a publisher, and get a letter back saying they’re not interested. But I learned a long time ago that you can’t take it to heart. Same goes with seeing some of the crap that does get published and getting bitter about you struggling to get people interested in your own work. You have to just keep your chin up and work on making your comics better, not worrying about the other factors. Most of the time, things will happen when they’re supposed to and you remind yourself that you’re making comics for the love of it. Anything else that happens is an added bonus!

Want more? See the index of “10 Questions” interviews.

Discuss “10 Questions” in the ComicsCareer.Com Forum.

Are you a professional comics creator? Participate in the 10 Questions project.

R. A. Jones is a Tulsa-based writer and editor who got his start in the comics business in the 1980’s. During that time he served as Executive Editor of Elite Comics, wrote for a wide variety of comics news magazines, including Amazing Heroes and Comics Buyer’s Guide.

R. A. Jones is a Tulsa-based writer and editor who got his start in the comics business in the 1980’s. During that time he served as Executive Editor of Elite Comics, wrote for a wide variety of comics news magazines, including Amazing Heroes and Comics Buyer’s Guide. Question 4: What do you do to recharge your creative batteries?

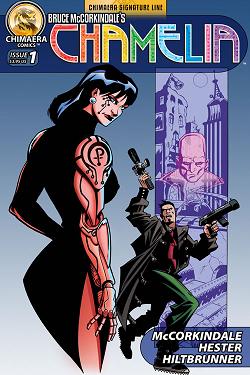

Question 4: What do you do to recharge your creative batteries? Writer. Penciller. Inker. Animator. Bruce McCorkindale has got you covered. He’s a multi-talented type from Omaha, Nebraska. His comics credits include writer/artist turns on The Falling Man, Negative Burn, and Chamelia. You’ve also seen his inking work on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Black Orchid, The Wretch, Rune Vs. Venom, Marvel Time Slip, and the current Image Comics series Golly! He also produces animation through his Action Impulse Studios.

Writer. Penciller. Inker. Animator. Bruce McCorkindale has got you covered. He’s a multi-talented type from Omaha, Nebraska. His comics credits include writer/artist turns on The Falling Man, Negative Burn, and Chamelia. You’ve also seen his inking work on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Black Orchid, The Wretch, Rune Vs. Venom, Marvel Time Slip, and the current Image Comics series Golly! He also produces animation through his Action Impulse Studios.